knitr::opts_chunk$set(echo = FALSE, message = FALSE, warning = FALSE)18 The WTO and Regional Trade Agreements (RTAs)

This chapter develops a conceptually grounded account of the long-run relationship between the multilateral trading system—first organized around the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and subsequently institutionalized through the World Trade Organization (WTO)—and the persistent proliferation of regional trade agreements (RTAs). The central claim is that regionalism is not an exogenous deviation from multilateralism but an endogenous response to the political economy of trade governance under heterogeneous preferences, sectoral distributional conflicts, and the increasing salience of “behind-the-border” policy domains. RTAs are legally permitted, politically demanded, and economically consequential precisely because the WTO’s foundational principles generate both stability and constraint: stability through non-discrimination and binding commitments, constraint through the difficulty of negotiating deep disciplines among an increasingly diverse membership.

The argument proceeds in five movements. The first reconstructs the legal and institutional logic of the GATT/WTO system, emphasizing the non-discrimination architecture—most-favored-nation (MFN) treatment and national treatment—and the tightly delimited conditions under which preferential arrangements are allowed. The second documents the historical growth and changing content of RTAs since 1948 and interprets this trajectory through canonical International Political Economy mechanisms, including domino dynamics, the shift from shallow to deep integration, and the political economy of rule design (Baldwin (2011); Dür, Baccini, and Elsig (2014); Horn, Mavroidis, and Sapir (2010)). The third revisits the “building blocks versus stumbling blocks” debate by linking Vinerian trade creation and diversion to endogenous protection incentives and to the prospects for multilateralization, while synthesizing the associated empirical record (Viner (1950); Bhagwati (1993); Freund and Ornelas (2010); Subramanian and Wei (2007)). The fourth examines the firm-level consequences of deep integration, with particular attention to how behind-the-border provisions affect multinational enterprises (MNEs), global value chains (GVCs), and foreign direct investment (FDI) (Antràs and Staiger (2012); Mattoo, Rocha, and Ruta (2020); Osnago, Rocha, and Ruta (2018)). The fifth develops regional case interpretations—North America, Europe, Latin America, Africa, and Asia—connecting legal form, economic outcomes, and governance constraints, and concludes by specifying conditions under which RTAs can complement, rather than fragment, multilateral cooperation (Baldwin and Low (2009); Hoekman and Mavroidis (2015)).

18.1 The GATT/WTO Architecture: Non-Discrimination and Conditional Exceptions

The multilateral trading system rests on two non-discrimination principles that jointly aim to reduce opportunistic discrimination and stabilize expectations. MFN treatment requires that any advantage granted by a member to the goods or services of another member be extended immediately and unconditionally to the like goods or services of all members. National treatment complements MFN by requiring that, once goods or services have entered a market, they be treated no less favorably than domestic counterparts. These principles are not merely legal abstractions. They serve as governance technologies that reduce strategic uncertainty for firms and constrain cycles of retaliation—functions that are central to the credibility of market access commitments in a world of repeated interaction (Jackson (1997); Hoekman and Kostecki (2009)).

MFN, however, is not absolute. The GATT embedded a controlled exception for customs unions and free-trade areas, conditional on liberalizing “substantially all the trade” among members and not raising barriers “on the whole” against outsiders, a legal compromise designed to reconcile preferential deepening with multilateral discipline. The 1979 “Enabling Clause” further codified a development-oriented permissiveness for preferential arrangements among developing economies and for generalized preference schemes. In services, the GATS permits economic integration agreements under conditions of substantial sectoral coverage and elimination of “substantially all” discrimination. Taken together, these provisions reflect a nesting logic: preferential liberalization is permitted, but it is normatively contained within a multilateral framework that remains anchored in non-discrimination (Hoekman and Mavroidis (2015)).

The WTO also developed surveillance tools aimed at disciplining regionalism through notification and peer review. The 2006 Transparency Mechanism, later reflected in WTO reporting practice, operationalizes this approach by requiring notification, enabling factual presentations, and providing a forum for discussion. The governance intention is explicit: preferentialism is tolerated insofar as it remains legible, reviewable, and broadly compatible with multilateral commitments.

18.2 The Proliferation and Transformation of RTAs since 1948

The expansion of RTAs is one of the most robust stylized facts of postwar trade governance. While early regional initiatives were concentrated in Europe, the late 1980s and 1990s witnessed a sharp acceleration of agreements, overlapping with the Uruguay Round and the creation of the WTO. The political economy logic of this acceleration has been articulated through “domino regionalism,” where preferential liberalization creates incentives for excluded actors to seek inclusion or negotiate parallel arrangements, generating cascades of agreement formation (Baldwin (1997); Baldwin (2011); Ethier (1998)).

Three transformations are particularly salient. First, participation became global, producing dense overlaps across memberships and obligations and giving empirical substance to the “spaghetti bowl” metaphor (Bhagwati (1995)). Second, the modal agreement shifted from tariff-centered liberalization to deeper governance packages incorporating services, investment, intellectual property, procurement, competition, and regulatory cooperation (Horn, Mavroidis, and Sapir (2010); Hofmann, Osnago, and Ruta (2017)). Third, the rise of GVCs increased the economic relevance of regulatory compatibility and services inputs, thereby making behind-the-border provisions central determinants of effective trade costs and of the location decisions of firms (Mattoo, Rocha, and Ruta (2020)).

18.3 Economic Logic: Building Blocks, Stumbling Blocks, and Endogenous Protection

Preferential agreements alter welfare through trade creation and trade diversion, the canonical mechanisms formalized by Viner (1950). Trade creation increases efficiency when preferences shift sourcing toward lower-cost suppliers inside the bloc. Trade diversion generates inefficiency when preferences redirect sourcing away from more efficient external suppliers. In contemporary settings, these channels interact with administrative frictions that are central to the practical meaning of preferentialism, notably rules of origin (ROOs), exemptions, and sectoral carve-outs. ROOs can either facilitate value-chain compatible cumulation or function as protectionist devices that neutralize preferences and impose compliance costs (Cadot and Melo (2008); Estevadeordal and Suominen (2008); Freund and Ornelas (2010)).

The systemic question is whether RTAs complement multilateralism or undermine it. The “building blocks” view emphasizes that RTAs can deliver liberalization and rules that are politically infeasible at the multilateral level and may trigger competitive liberalization dynamics consistent with multilateralization over time (Bhagwati (1993); Baldwin (2011)). The “stumbling blocks” view stresses the political economy risk that insiders develop vested interests in maintaining discrimination and that overlapping obligations increase complexity and weaken multilateral discipline (Bhagwati (1995); Limão (2006)). A more design-centered synthesis recognizes heterogeneity: depth, transparency, enforceability, and external orientation vary, so systemic effects cannot be inferred from a single archetype (Dür, Baccini, and Elsig (2014); Hofmann, Osnago, and Ruta (2017)).

The empirical record reinforces conditionality. On the WTO itself, the literature moved from skepticism to evidence that the GATT/WTO increased trade substantially but unevenly, depending on bindings and participation patterns (Rose (2004); Subramanian and Wei (2007)). On RTAs, average effects on intra-bloc trade are commonly positive, with stronger effects where agreements include deeper provisions, although restrictive ROOs and carve-outs can attenuate gains and shape the organization of production and sourcing (Hofmann, Osnago, and Ruta (2017); Mattoo, Rocha, and Ruta (2020)).

18.4 From Shallow to Deep Integration: Rule Design and Regulatory Governance

The evolution from shallow to deep integration is central to the contemporary meaning of RTAs. Deep RTAs increasingly regulate policies that shape effective trade costs: investment regimes, services market access, technical barriers to trade, SPS measures, procurement, and regulatory cooperation. This shift reflects both economic structure and political strategy. Economically, task fragmentation and GVCs make the trade costs embedded in domestic regulation more important than border tariffs. Politically, RTAs function as venues for rule-making when multilateral negotiations are slow or blocked (Horn, Mavroidis, and Sapir (2010); Mattoo, Rocha, and Ruta (2020)).

ROOs are pivotal because they connect legal preferences to firm-level sourcing decisions. Cumulation provisions, by contrast, can align legal design with the geography of value chains and reduce the distortionary impact of overlapping agreements. In this sense, cumulation is not a technical detail but a governance instrument that influences whether regionalism remains exclusive or becomes diffusible.

18.5 Multinationals, GVCs, and FDI: How RTAs Rewire Production

Deep RTAs matter because firms internalize governance conditions when organizing production across borders. When agreements reduce policy uncertainty, standardize regulatory interfaces, and improve services market access, they alter the relative cost of exporting versus investing and thus affect both trade and FDI. The logic linking offshoring, contracts, and agreement design is formalized in the theory of trade agreements under fragmentation and cross-border production (Antràs and Staiger (2012)) and is empirically consistent with findings that deep provisions correlate with greater vertical FDI and more complex sourcing patterns (Osnago, Rocha, and Ruta (2018); Mattoo, Rocha, and Ruta (2020)). The distributional consequences are equally geoeconomic: deep agreements can anchor regional production hubs, induce preference erosion for outsiders, and generate incentives for accession or parallel negotiations, thereby shaping the spatial organization of global production.

18.6 Regional Interpretations

North America remains a canonical illustration of how regional integration reorganizes trade and production. The Canada–United States Free Trade Agreement and NAFTA contributed to the expansion of regional value chains, with documented productivity and wage effects in Canada associated with tariff reductions (Trefler (2004)) and broader evidence on integration dynamics in North America and beyond (Lederman, Maloney, and Servén (2005)). The USMCA illustrates the contemporary shift toward deeper governance domains, including digital trade and revised ROOs, and it provides a case in which legal design explicitly aims to shape firm behavior by tightening origin requirements.

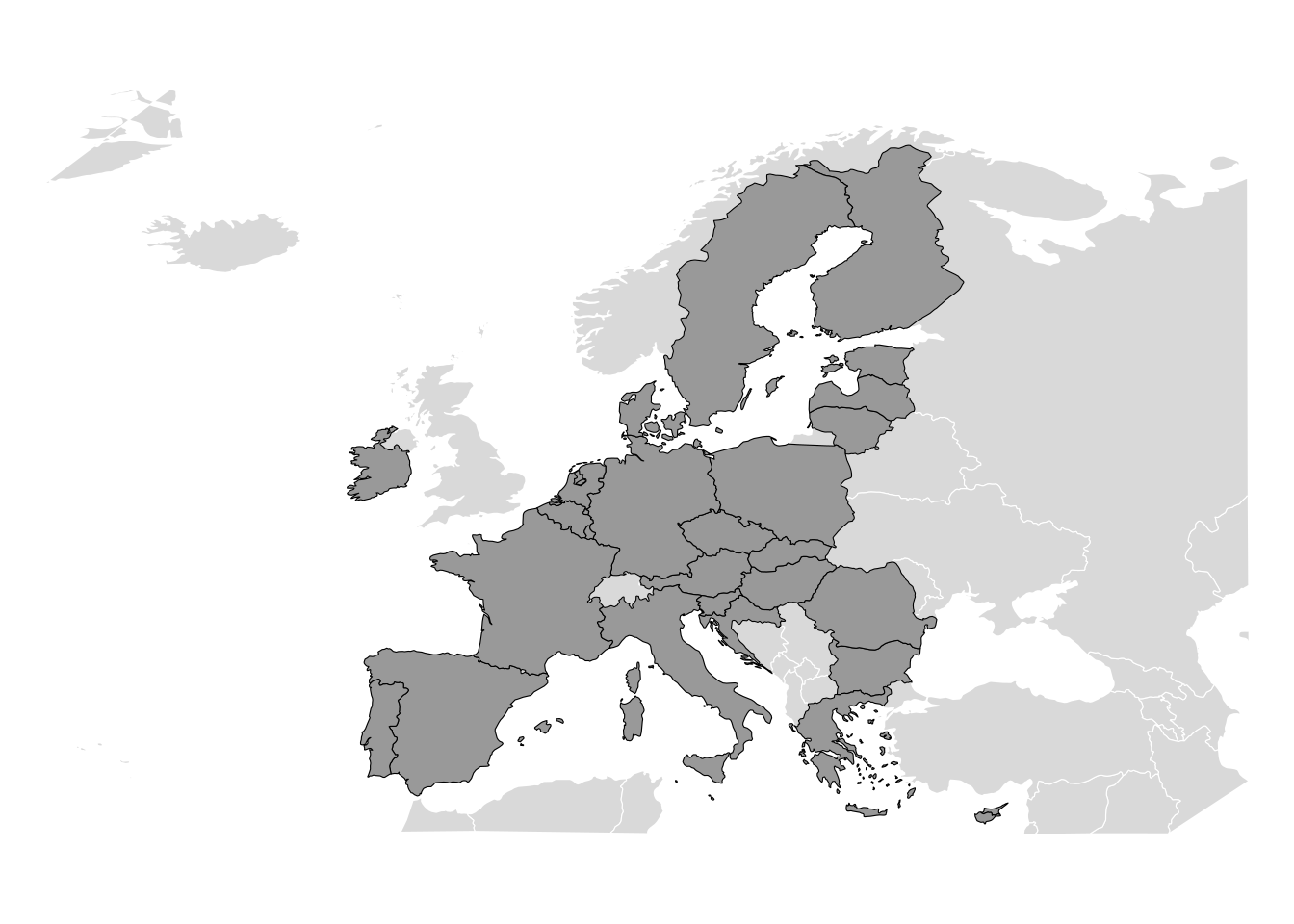

18.7 Europe: From Customs Union to Regulatory Power

Europe constitutes the most institutionally dense experiment in regionalism, and therefore the clearest illustration of how RTAs can become an internal market project rather than a tariff bargain. The European Union’s distinctive feature is the combination of deep negative integration (removal of internal barriers) with positive integration (the creation of common rules, enforcement mechanisms, and supranational adjudication). In geoeconomic terms, this architecture matters because it reduces not only border frictions but also regulatory uncertainty, thereby enabling firms to organize production and distribution as if operating within a quasi-domestic market.

A simple descriptive indicator captures the resulting degree of internalization: for most EU member states, intra-EU exports represent the majority of total exports. Eurostat reports that, in 2024, most EU countries recorded intra-EU export shares between 50% and 75%, with several economies above 75% (for instance Luxembourg at 81% and Czechia at 79%), while only a small number, such as Cyprus and Ireland, had intra-EU export shares below 50% (Eurostat (2025)). This pattern is not merely an outcome of proximity; it reflects a governance achievement. By stabilizing rules across a large jurisdiction, the EU effectively converts geographic closeness into routinized market integration, producing high levels of intra-regional trade intensity that resemble those of a continental economy rather than a loose preferential area.

Externally, the EU’s common commercial policy and its network of preferential agreements extend this governance capacity beyond its borders. The geoeconomic significance lies in the EU’s role as a rule-maker: the ability to diffuse standards through market size and regulatory conditionality. In this sense, Europe exemplifies a path in which regionalism is not primarily a substitute for multilateralism, but a mechanism for generating enforceable rules that can be projected outward, sometimes complementing WTO disciplines and sometimes substituting for stalled multilateral negotiations. The systemic consequence is ambiguous: EU rule export can raise global baselines when adopted widely, but it can also contribute to fragmentation when external partners face competing rule systems and compliance costs.

18.8 Latin America: MERCOSUR, Partial-Scope Regionalism, and Implementation Constraints

Latin American regionalism has historically been characterized by ambitious legal design confronting binding constraints of implementation capacity, macroeconomic volatility, and heterogeneous national development strategies. Early projects such as LAFTA and its successor LAIA institutionalized flexible, partial-scope arrangements, often prioritizing political symbolism and gradualism over enforceable integration. MERCOSUR, created in 1991, marked a shift toward more formal commitments among a subset of countries, but its trajectory illustrates why regionalism’s economic effects are design- and context-dependent rather than automatic (Devlin and Estevadeordal (2001)).

A descriptive indicator illustrates MERCOSUR’s persistent challenge: intra-bloc trade has remained comparatively low and has trended downward relative to extra-bloc trade. A recent official presentation based on MERCOSUR Secretariat and national statistical sources reports that intra-zone exports in early 2024 were only slightly above 10% of total MERCOSUR exports, described as among the lowest shares since the bloc’s creation (Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores, Comercio Internacional y Culto (Argentina) (2024)). This contrasts sharply with the European pattern and highlights a central geoeconomic point: preferential tariff commitments do not necessarily translate into dense regional production networks unless they are complemented by stable macroeconomic conditions, predictable rules, trade facilitation, and sufficient infrastructure connectivity. Where these complements are weak, firms continue to organize supply and sales around extra-regional markets, and regional agreements become less about internal production integration and more about external bargaining positions and selective sectoral protections.

Latin America thus offers an instructive case for the “stumbling blocks” concern: when regional agreements do not generate deep market integration, they can nonetheless generate complex obligations and distributional conflicts without producing the network densification that would otherwise encourage rule diffusion and multilateralization. The appropriate conclusion is not that Latin American regionalism is futile, but that its geoeconomic payoff is conditional on implementation quality and on whether agreement design targets the practical frictions that matter for firms, notably logistics, border administration, and regulatory predictability.

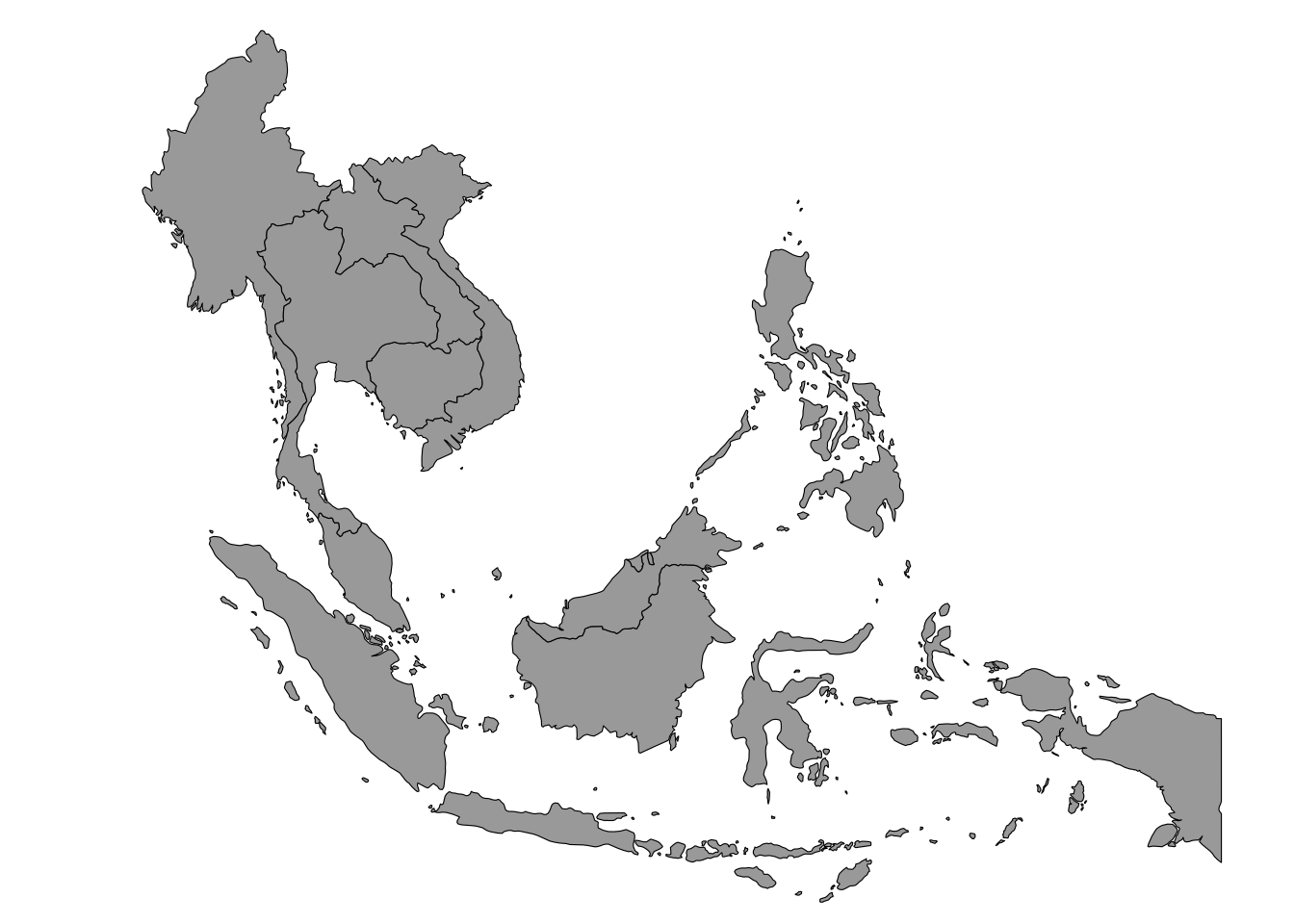

18.9 Asia and the Pacific: ASEAN Centrality, Open Regionalism, and Value-Chain Governance

Asian regionalism has evolved through layered architectures rather than a single institutional center. ASEAN has functioned as a hub around which multiple “ASEAN+1” arrangements have developed, while broader frameworks have sought to reconcile preferential integration with outward orientation. The geoeconomic logic is the management of connectivity: Asia’s growth model has been deeply associated with GVC participation, and the region’s agreements have increasingly aimed to stabilize the governance of cross-border production, particularly by reducing policy uncertainty in services, investment, and trade facilitation (Ravenhill (2010); Baldwin (2011)).

Descriptive trade data illustrate both the region’s integration and its limits. ASEAN statistical reporting indicates that intra-ASEAN trade accounted for about 22.3% of total ASEAN trade in 2022, and that the intra-ASEAN share remained around that magnitude despite fluctuations in overall trade volumes (ASEANstats (2023)). This share is substantial in absolute value but also reveals the continued importance of extra-regional demand and production linkages, especially with China, the United States, and the European Union. Geoeconomically, the implication is that Asian regionalism has often been “production-network compatible” without being fully “inward integrating” in the European sense: the goal has not been to replace global markets with a regional market, but to stabilize and diversify the terms under which production networks operate, especially under conditions of strategic rivalry and supply-chain risk.

This pattern also clarifies why Asia has been a key laboratory for deep provisions linked to value chains. When intermediate goods cross borders multiple times, the economic relevance of tariffs is often secondary to the relevance of customs administration, standards, services inputs, and investment regimes. Regional agreements become instruments for reducing the effective thickness of borders, rather than instruments for constructing a closed bloc.

18.10 Africa: Overlapping Regionalism, AfCFTA, and the Political Economy of Connectivity

Africa’s regionalism has long been characterized by multiple, overlapping regional economic communities, varying depth of commitments, and substantial infrastructure and capacity constraints. In geoeconomic terms, the central issue is not the existence of tariff preferences but the high fixed costs of cross-border exchange: transport costs, border delays, fragmented standards, and limited trade finance. These frictions weaken the capacity of preferential agreements to generate the cumulative effects observed in regions where logistics and administrative systems are more integrated.

A basic empirical regularity captures the challenge. ECA reporting indicates that intra-African trade remains low by global standards and that its share declined from 14.5% in 2021 to 13.7% in 2022 (United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (2024)). Such figures signal structural dependence on extra-continental markets and exposure to external shocks—precisely the vulnerability that continental integration initiatives aim to reduce. The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) is therefore best interpreted as a strategic attempt to reconfigure economic geography: expanding market size, improving bargaining leverage, and creating conditions for regional value chain development by reducing fragmentation.

Yet the political economy constraints are binding. Overlapping memberships create complex obligations, and implementation capacity varies widely. Moreover, infrastructure deficits and border administration costs can exceed tariff barriers in economic significance. As a result, the geoeconomic promise of AfCFTA depends critically on whether integration efforts prioritize trade facilitation, corridor development, and credible enforcement mechanisms, rather than relying primarily on preferential tariffs. UNECA’s integration assessments emphasize precisely these constraints and the centrality of competitiveness and innovation for translating legal commitments into effective market integration (United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (2016)).

The African case thereby sharpens the chapter’s broader conclusion: regionalism complements multilateralism and produces welfare-enhancing densification of trade networks when it reduces the frictions that matter for firms and when its design supports outward orientation, transparency, and feasible implementation. Where these conditions fail, agreements may remain thin legal layers over persistent structural barriers, with limited capacity to alter production geographies.

18.11 Conclusion

The WTO’s MFN and national treatment obligations remain the normative core of the trading system, yet the proliferation of RTAs has transformed the channels through which liberalization and rule-making proceed. WTO law is permissive but conditional: preferential arrangements are allowed as deviations from MFN, but they are expected to liberalize comprehensively and to avoid raising barriers against outsiders on the whole. The empirical record indicates that regionalism is extensive, heterogeneous, and increasingly deep. Its welfare and systemic effects are design-dependent, shaped by breadth, ROOs, cumulation, transparency, and enforcement, and conditioned by domestic political economy constraints that determine implementation.

Two implications follow. When RTAs adopt outward-oriented designs, align ROOs with value-chain realities, and provide transparent and enforceable disciplines, they are more likely to complement multilateralism and facilitate diffusion of rules. When they generate rents through restrictive ROOs, carve-outs, and opaque governance, they heighten diversionary risks and contribute to fragmentation. The multilateral and regional logics are not inherently antagonistic; their relationship is mediated by institutional design and by the political economy of compliance and enforcement (Freund and Ornelas (2010); Hoekman and Mavroidis (2015); Mattoo, Rocha, and Ruta (2020)).